We've spent a lot of collective time and effort on design and policy to support the privacy of the user of a piece of software, whether it's the Web or a mobile app or a device. But more current and more challenging is the privacy of the non-user of the app, the privacy of the bystander. With the ubiquity of sensors, we are increasingly observed, not just by giant corporations or government agencies, but by, as they say, little brothers.

Consider the smartphone camera. Taking digital photos is free, quick and easy; resolution and quality increase; metadata (like precise geolocation) is attached; sharing those photos is easy via online services. As facial recognition has improved, it has become easier to automatically identify the people depicted in a photo, whether they're the subject of a portrait or just in the background. If you don't want to share records of your precise geolocation and what you're doing in public places, with friends, family, strangers and law enforcement, it's no longer enough to be careful with the technology you choose to use, you'd also have to be constantly vigilant about the technology that everyone around you is using.

While it may be tempting to draw a "throw your hands up" conclusion from this -- privacy is dead, get over it, there's nothing we can easily do about it -- we actually have widespread experience with this kind of value and various norms to protect it. At conferences and public events, it's not uncommon to have a system of stickers on nametags to either opt-in or opt-out of photos. This is a help (not a hindrance) for event photographers: rather than asking everyone to pose in your photo, or asking everyone after the fact if they're alright with your posting a public photo, or being afraid of posting a photo and facing the anger of your attendees, you can just keep an eye on the red and green dots on those plastic nametags and feel confident that you're respecting the attendees at your event.

There are similar norms in other settings. Taking video in the movie theater violates legal protections, but there are also widespread and reasonably well-enforced norms against capturing video of live theater productions or comedians who test out new material in clubs, on grounds that may not be copyright. Art museums will often tell you whether photos are welcome or prohibited. In some settings the privacy of the people present is so essential that unwritten or written rules prohibit cameras altogether: at nude hot springs, for example, you just can't use a camera at all. You wouldn't take a photo in the waiting room of your doctor's office and you'll invite anger and social confrontation if you're taking photos of other people's children at your local playground.

And even in "public" or in contexts with friends, there are spoken or unspoken expectations. "Don't post that photo of me drinking, please." "Let me see how I look in that before you post it on Facebook." "Everyone knows that John doesn't like to have his photo taken."

As cameras become small and more widely used, and encompass depictions of more people, and are shared more widely and easily, and identifications of depicted people can also be shared, our social norms and spoken discussions don't easily keep up. Checking with people before you post a photo of them is absolutely a good practice and I encourage you to follow it. But why not also use technology to facilitate this checking others' preferences?

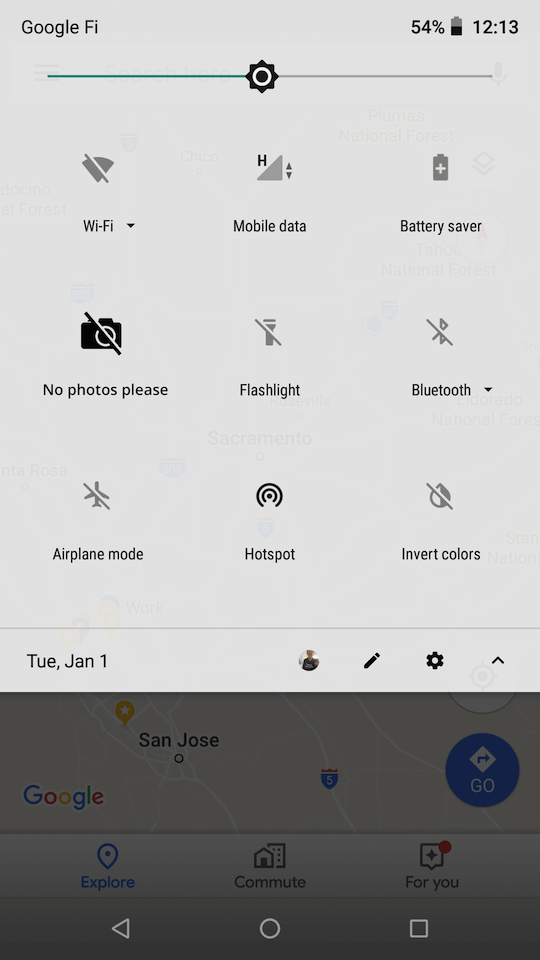

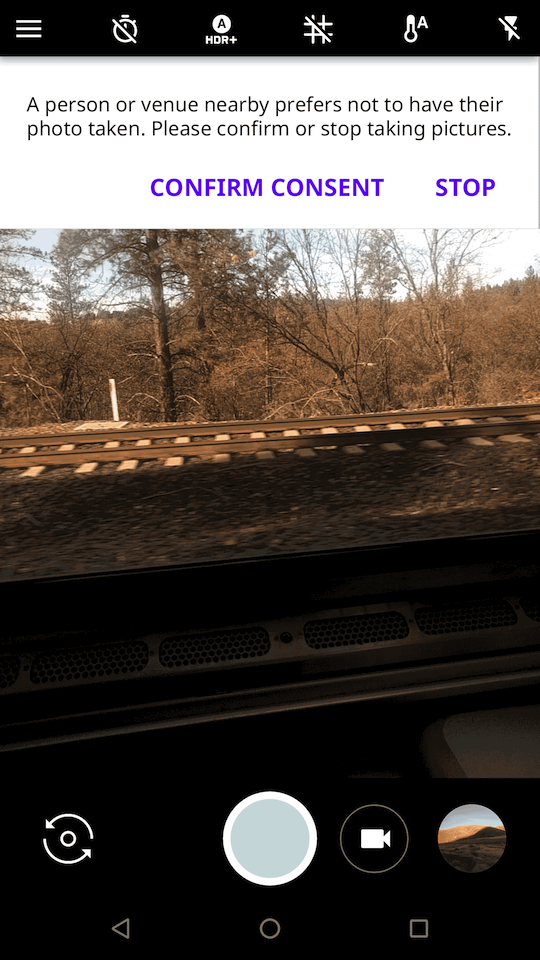

We have all the tools we need to make "no photos please" nametag stickers into unobtrusive and efficiently communicated messages. If you're attending a conference or party and don't want people to take your photo, just tap the "no photos please" setting on your smartphone before you walk in. And if you're taking photos at an event, your camera will show a warning when it knows that someone in the room doesn't want their photo taken, so that you can doublecheck with the people in your photo and make sure you're not inadvertently capturing someone in the background. And the venue can remind you that way too, in case you don't know the local norm that pictures shouldn't be taken in the church or museum.

As a technical matter, I think we're looking at Bluetooth broadcast beacons, from smartphones or stationary devices. That could be a small Arduino-based widget on the wall of a commercial venue, or one day you might have a poker-chip-sized device in your pocket that you can click into private mode. When you're using a compatible camera app on your phone or a compatible handheld camera, your device regularly scans for nearby Bluetooth beacons and if it sees a "no photos please" message, it shows a (dismissable) warning.

The discretionary communication of preferences is ideal in part because it isn't self-enforcing. For example, if the police show up at the political protest you're attending and broadcast a "no photos please" beacon, you can (and should) override your camera warning to take photos of their official activity, as a safeguard for public safety and accountability. An automatically-enforcing DRM-style system would be both infeasible to construct and, if it were constructed, inappropriately inviting to government censorship or aggressive copyright maximalism. Technological hints are also less likely to confusingly over-promise a protection: we can explain to people that the "no photos please" beacon doesn't prevent impolite or malicious people from surreptitiously taking your photo, just as people are extremely familiar with the fact that placards, polite requests and even laws are sometimes ignored.

Making preferences technically available could also help with legal compliance. If you're taking a photo at an event and get a "no photos" warning, your device UI can help you log why you might be taking the photo anyway. Tap "I got consent" and your camera can embed metadata in the file that you gathered consent from the depicted people. Tap "Important public purpose" at the protest and you'll have a machine-readable affirmation in place of what you're doing, and your Internet-connected phone can also use that signal to make sure photos in this area are promptly backed up securely in case your device is confiscated.

People's preferences are of course more complicated than just "no photos please" or "sure, take my photo". While I, like many, have imagined that sticky policies could facilitate rules of how data is subsequently shared and used, there are good reasons to start with the simple capture-time question. For one, it's familiar, from these existing social and legal norms. For another, it can be a prompt for real-time in-person conversation. Rather than assuming an error-free technical-only system of preference satisfaction, this can be a quick reminder to check with the people right there in front of you for those nuances, and to do so prior to making a digital record.

Broadcast messages provide opportunities that I think we haven't fully explored or embraced in the age of the Internet and the (rightfully lauded) end-to-end principle. Some communications just naturally take the form of letting people in a geographic area know something relevant to the place. "The cafe is closing soon." "What's the history of that statue?" "What's the next stop on this train and when are we scheduled to arrive?" If WiFi routers included latitude and longitude in the WiFi network advertisement, your laptop could quickly and precisely geolocate even in areas where you don't have Internet access, and do so passively, without broadcasting your location to a geolocation provider. (That one is a little subtle; we wrote a paper on it back when we were evaluating the various privacy implications of WiFi geolocation databases at Berkeley.) What about, "Anyone up for a game of chess?" (See also, Grindr.) eBook readers could optionally broadcast the title of the current book to re-create the lovely serendipity of seeing the book cover a stranger is reading on the train. Music players could do the same.

The Internet is amazing for letting us communicate with people around the world around shared interests. We should see the opportunity for networking technology to also facilitate communications, including conversations about privacy, with those nearby.

Some end notes that my head wants to let go of: There is some prior art here that I don't want to dismiss or pass over, I just think we should push it further. A couple examples:

- Google folks have developed broadcast URLs that they call The Physical Web so that real-life places can share a Web page about them (over mDNS or Bluetooth Low Energy) and I hope one day we can get a link to the presenter's current slide using networking rather than everyone taking a picture of a projected URL and awkwardly typing it into our laptops later.

- The Occupy movement showed an interest in geographically-located Web services, including forums and chatrooms that operate over WiFi but not connected to the Internet. Occupy Here:

Anyone within range of an Occupy.here wifi router, with a web-capable smartphone or laptop, can join the network “OCCUPY.HERE,” load the locally-hosted website http://occupy.here, and use the message board to connect with other users nearby.

Getting a little further afield but still related, it would be helpful if the network provider could communicate directly with the subscriber using the expressive capability of the Web. Lacking this capability, we've seen frustrating abuses of interception: captive portals redirect and impersonate Web traffic; ISPs insert bandwidth warnings as JavaScript insecurely transplanted into HTTP pages. Why not instead provide a way for the network to push a message to the client, not by pretending to be a server you happen to connect to around that same time, but just as a clearly separate message? ICMP control messages are an existing but underused technology.