From: nick@npdoty.name

Date: 1/01/2019 01:30:00 PM Bcc: https://bcc.npdoty.name/

We've spent a lot of collective time and effort on design and policy to support the privacy of the user of a piece of software, whether it's the Web or a mobile app or a device. But more current and more challenging is the privacy of the non-user of the app, the privacy of the bystander. With the ubiquity of sensors, we are increasingly observed, not just by giant corporations or government agencies, but by, as they say, little brothers.

Consider the smartphone camera. Taking digital photos is free, quick and easy; resolution and quality increase; metadata (like precise geolocation) is attached; sharing those photos is easy via online services. As facial recognition has improved, it has become easier to automatically identify the people depicted in a photo, whether they're the subject of a portrait or just in the background. If you don't want to share records of your precise geolocation and what you're doing in public places, with friends, family, strangers and law enforcement, it's no longer enough to be careful with the technology you choose to use, you'd also have to be constantly vigilant about the technology that everyone around you is using.

While it may be tempting to draw a "throw your hands up" conclusion from this -- privacy is dead, get over it, there's nothing we can easily do about it -- we actually have widespread experience with this kind of value and various norms to protect it. At conferences and public events, it's not uncommon to have a system of stickers on nametags to either opt-in or opt-out of photos. This is a help (not a hindrance) for event photographers: rather than asking everyone to pose in your photo, or asking everyone after the fact if they're alright with your posting a public photo, or being afraid of posting a photo and facing the anger of your attendees, you can just keep an eye on the red and green dots on those plastic nametags and feel confident that you're respecting the attendees at your event.

There are similar norms in other settings. Taking video in the movie theater violates legal protections, but there are also widespread and reasonably well-enforced norms against capturing video of live theater productions or comedians who test out new material in clubs, on grounds that may not be copyright. Art museums will often tell you whether photos are welcome or prohibited. In some settings the privacy of the people present is so essential that unwritten or written rules prohibit cameras altogether: at nude hot springs, for example, you just can't use a camera at all. You wouldn't take a photo in the waiting room of your doctor's office and you'll invite anger and social confrontation if you're taking photos of other people's children at your local playground.

And even in "public" or in contexts with friends, there are spoken or unspoken expectations. "Don't post that photo of me drinking, please." "Let me see how I look in that before you post it on Facebook." "Everyone knows that John doesn't like to have his photo taken."

As cameras become small and more widely used, and encompass depictions of more people, and are shared more widely and easily, and identifications of depicted people can also be shared, our social norms and spoken discussions don't easily keep up. Checking with people before you post a photo of them is absolutely a good practice and I encourage you to follow it. But why not also use technology to facilitate this checking others' preferences?

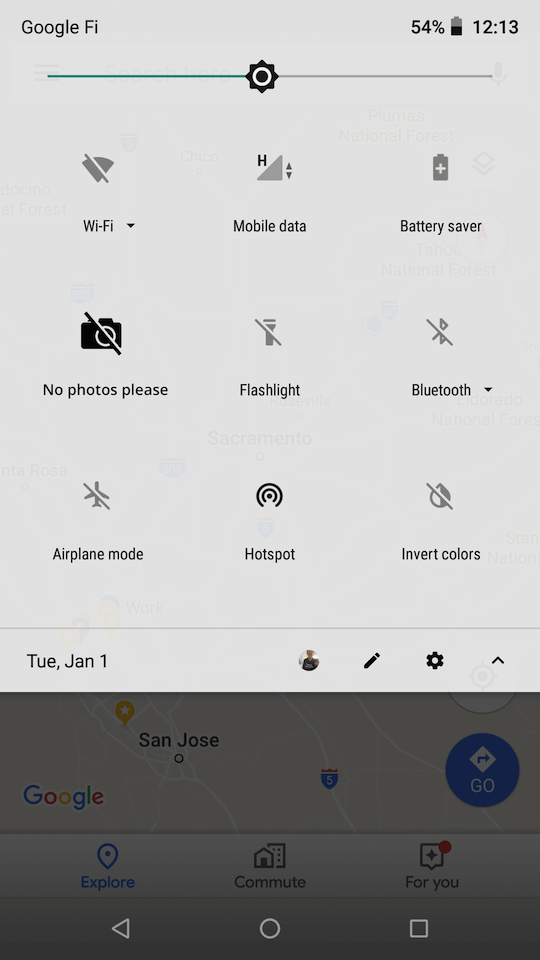

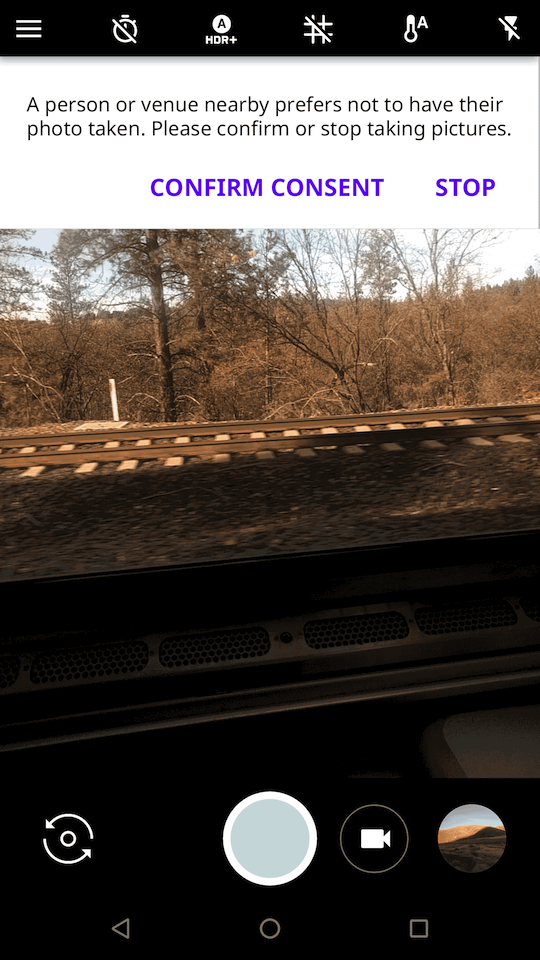

We have all the tools we need to make "no photos please" nametag stickers into unobtrusive and efficiently communicated messages. If you're attending a conference or party and don't want people to take your photo, just tap the "no photos please" setting on your smartphone before you walk in. And if you're taking photos at an event, your camera will show a warning when it knows that someone in the room doesn't want their photo taken, so that you can doublecheck with the people in your photo and make sure you're not inadvertently capturing someone in the background. And the venue can remind you that way too, in case you don't know the local norm that pictures shouldn't be taken in the church or museum.

As a technical matter, I think we're looking at Bluetooth broadcast beacons, from smartphones or stationary devices. That could be a small Arduino-based widget on the wall of a commercial venue, or one day you might have a poker-chip-sized device in your pocket that you can click into private mode. When you're using a compatible camera app on your phone or a compatible handheld camera, your device regularly scans for nearby Bluetooth beacons and if it sees a "no photos please" message, it shows a (dismissable) warning.

The discretionary communication of preferences is ideal in part because it isn't self-enforcing. For example, if the police show up at the political protest you're attending and broadcast a "no photos please" beacon, you can (and should) override your camera warning to take photos of their official activity, as a safeguard for public safety and accountability. An automatically-enforcing DRM-style system would be both infeasible to construct and, if it were constructed, inappropriately inviting to government censorship or aggressive copyright maximalism. Technological hints are also less likely to confusingly over-promise a protection: we can explain to people that the "no photos please" beacon doesn't prevent impolite or malicious people from surreptitiously taking your photo, just as people are extremely familiar with the fact that placards, polite requests and even laws are sometimes ignored.

Making preferences technically available could also help with legal compliance. If you're taking a photo at an event and get a "no photos" warning, your device UI can help you log why you might be taking the photo anyway. Tap "I got consent" and your camera can embed metadata in the file that you gathered consent from the depicted people. Tap "Important public purpose" at the protest and you'll have a machine-readable affirmation in place of what you're doing, and your Internet-connected phone can also use that signal to make sure photos in this area are promptly backed up securely in case your device is confiscated.

People's preferences are of course more complicated than just "no photos please" or "sure, take my photo". While I, like many, have imagined that sticky policies could facilitate rules of how data is subsequently shared and used, there are good reasons to start with the simple capture-time question. For one, it's familiar, from these existing social and legal norms. For another, it can be a prompt for real-time in-person conversation. Rather than assuming an error-free technical-only system of preference satisfaction, this can be a quick reminder to check with the people right there in front of you for those nuances, and to do so prior to making a digital record.

Broadcast messages provide opportunities that I think we haven't fully explored or embraced in the age of the Internet and the (rightfully lauded) end-to-end principle. Some communications just naturally take the form of letting people in a geographic area know something relevant to the place. "The cafe is closing soon." "What's the history of that statue?" "What's the next stop on this train and when are we scheduled to arrive?" If WiFi routers included latitude and longitude in the WiFi network advertisement, your laptop could quickly and precisely geolocate even in areas where you don't have Internet access, and do so passively, without broadcasting your location to a geolocation provider. (That one is a little subtle; we wrote a paper on it back when we were evaluating the various privacy implications of WiFi geolocation databases at Berkeley.) What about, "Anyone up for a game of chess?" (See also, Grindr.) eBook readers could optionally broadcast the title of the current book to re-create the lovely serendipity of seeing the book cover a stranger is reading on the train. Music players could do the same.

The Internet is amazing for letting us communicate with people around the world around shared interests. We should see the opportunity for networking technology to also facilitate communications, including conversations about privacy, with those nearby.

Some end notes that my head wants to let go of: There is some prior art here that I don't want to dismiss or pass over, I just think we should push it further. A couple examples:

- Google folks have developed broadcast URLs that they call The Physical Web so that real-life places can share a Web page about them (over mDNS or Bluetooth Low Energy) and I hope one day we can get a link to the presenter's current slide using networking rather than everyone taking a picture of a projected URL and awkwardly typing it into our laptops later.

- The Occupy movement showed an interest in geographically-located Web services, including forums and chatrooms that operate over WiFi but not connected to the Internet. Occupy Here:

Anyone within range of an Occupy.here wifi router, with a web-capable smartphone or laptop, can join the network “OCCUPY.HERE,” load the locally-hosted website http://occupy.here, and use the message board to connect with other users nearby.

Getting a little further afield but still related, it would be helpful if the network provider could communicate directly with the subscriber using the expressive capability of the Web. Lacking this capability, we've seen frustrating abuses of interception: captive portals redirect and impersonate Web traffic; ISPs insert bandwidth warnings as JavaScript insecurely transplanted into HTTP pages. Why not instead provide a way for the network to push a message to the client, not by pretending to be a server you happen to connect to around that same time, but just as a clearly separate message? ICMP control messages are an existing but underused technology.

Labels: broadcast, wifi, privacy

From: npdoty@ischool.berkeley.edu

Date: 6/06/2018 05:05:00 PM To: Seb Benthall Bcc: https://bcc.npdoty.name/

In thinking about group governance practices, it seems like setting out explicit norms can be broadly useful, no matter the particular history that's motivated the adoption of those norms. In a way, it's a common lesson of open source collaborative practice: documentation is essential.

I have to admit that though I’m quite glad that we have a Code of Conduct now in BigBang, I’m uncomfortable with the ideological presumptions of its rationale and the rejection of ‘meritocracy’.

For what it's worth, I don't think this is an ideological presumption, but an empirical observation. Lots of people have noticed lots of open source communities where the stated goal of decision-making by "meritocracy" has apparently contributed to a culture where homogeneity is preferred (because maybe you measure the vague concept of "merit" in some ways by people who behave most similarly to you) and where harassment is tolerated (because if the harasser has some merit -- again, on that fuzzy scale -- maybe that merit could outweigh the negative consequences of their behavior).

I don't see the critiques of meritocracy as relativistic; that is, it's not an argument that there is no such thing as merit, that nothing can be better than something else. It's just a recognition that many implementations of claimed meritocracy aren't very systematic about evaluation of merit and that common models tend to have side effects that are bad for working communities, especially for communities that want to attract participants from a range of situations and backgrounds, where online collaboration can especially benefit.

To that point, you don't need to mention "merit" or "meritocracy" at all in writing a code of conduct and establishing such a norm doesn't require having had those experiences with "meritocratic" projects in the past. Having an established norm of inclusivity makes it easier for everyone. We don't have to decide on a case-by-case basis whether some harassing behavior needs to be tolerated by, for example, weighing the harm against the contributions of the harasser. When you start contributing to a new project, you don't have to just hope the leadership of that project shares your desire for respectful behavior. Instead, we just agree that we'll follow simple rules and anyone who wants to join in can get a signal of what's expected. Others have tried to describe why the practice can be useful in countering obstacles faced by underrepresented groups, but the tool of a Code of Conduct is in any case useful for all.

Could we use forking as a mechanism for promoting inclusivity rather than documenting a norm? Perhaps; open source projects could just fork whenever it became clear that a contributor was harassing other participants, and that capability is something of a back stop if, for example, harassment occurs and project maintainers do nothing about it. But that only seems effective (and efficient) if the new fork established a code of conduct that set a different expectation of behavior; without the documentary trace (a hallmark of open source software development practice) others can't benefit from that past experience and governance process. While forking is possible in open source development, we don't typically want to encourage it to happen rapidly, because it introduces costs in dividing a community and splitting their efforts. Where inclusivity is a goal of project maintainers, then, it's easier to state that norm up front, just like we state the license up front, and the contribution instructions up front, and the communication tools up front, rather than waiting for a conflict and then forking both the code and collaborators at each decision point. And if a project has a goal of broad use and participation, it wants to demonstrate inclusivity towards casual participants as well as dedicated contributors. A casual user (who provides documentation, files bugs, uses the software and contributes feedback on usability) isn't likely to fork an open source library that they're using if they're treated without respect, they'll just walk away instead.

It could be that some projects (or some developers) don't value inclusivity. That seems unusual for an open source project since such projects typically benefit from increased participation (both at the level of core contributers and at lower-intensity users who provide feedback) and online collaboration typically has the advantage of bringing in participation from outside one's direct neighbors and colleagues. But for the case of the happy lone hacker model, a Code of Conduct might be entirely unnecessary, because the lone contributor isn't interested in developing a community, but instead just wishes to share the fruits of a solitary labor. Permissive licensing allows interested groups with different norms to build on that work without the original author needing to collaborate at all -- and that's great, individuals shouldn't be pressured to collaborate if they don't want to. Indeed, the choice to refuse to set community norms is itself an expression which can be valuable to others; development communities who explicitly refuse to codify norms or developers who refuse to abide by them do others a favor by letting them know what to expect from potential collaboration.

Thanks for the interesting conversation,

Nick

Labels: inclusivity, codeofconduct, governance, bigbang, meritocracy, opensource

From: nick@npdoty.name

Date: 1/14/2018 03:58:00 PM To: myself, others in my industry Bcc: https://bcc.npdoty.name/

A reminder:

Unconstrained media access to a person is indistinguishable from harassment.

It pains me to watch my grandfather suffer from surfeit of communication. He can't keep up with the mail he receives each day. Because of his noble impulse to charity and having given money to causes he supports (evangelical churches, military veterans, disadvantaged children), those charities sell his name for use by other charities (I use "charity" very loosely), and he is inundated with requests for money. Very frequently, those requests include a "gift", apparently in order to induce a sense of obligation: a small calendar, a pen and pad of paper, refrigerator magnets, return address labels, a crisp dollar bill. Those monetary ones surprised me at first, but they are common and if some small percentage of people feel an obligation to write a $50 check, then sending out a $1 to each person makes it worth their while (though it must not help the purported charitable cause very much, not a high priority). Many now include a handful of US coins stuck to the response card -- ostensibly to imply that just a few cents a day can make a difference, but, I suspect, to make it harder to recycle the mail directly because it includes metal as well as paper. (I throw these in the recycling anyway.) Some of these solicitations include a warning on the outside that I hadn't seen before, indicating that it's a federal criminal offense to open postal mail or to keep it from the recipient. Perhaps this is a threat to caregivers to discourage them from throwing away this junk mail for their family members; I suspect more likely, it encourages the suspicion in the recipient that someone might try to filter their mail, and that to do so would be unjust, even criminal, that anyone trying to help them by sorting their mail should not be trusted. It disgusts me.

But the mails are nothing compared to the active intrusiveness of other media. Take conservative talk radio, which my grandfather listened to for years as a way to keep sound in the house and fend off loneliness. It's often on in the house at a fairly low volume, but it's ever present, and it washes over the brain. I suspect most people could never genuinely understand Rush Limbaugh's rants, but coherent argument is not the point, it's just the repetition of a claim, not even a claim, just a general impression. For years, my grandfather felt conflicted, as many of his beloved family members (liberal and conservative) worked for the federal government, but he knew, in some quite vague but very deep way, that everyone involved with the federal government was a menace to freedom. He tells me explicitly that if you hear something often enough, you start to think it must be true.

And then there's the TV, now on and blaring 24 hours a day, whether he's asleep or awake. He watches old John Wayne movies or NCIS marathons. Or, more accurately, he watches endless loud commercials, with some snippets of quiet movies or television shows interspersed between them. The commercials repeat endlessly throughout the day and I start to feel confused, stressed and tired within a few hours of arriving at his house. I suspect advertisers on those channels are happy with the return they receive; with no knowledge of the source, he'll tell me that he "really ought to" get or try some product or another for around the house. He can't hear me, or other guests, or family he's talking to on the phone when a commercial is on, because they're so loud.

Compared to those media, email is clear and unintrusive, though its utility is still lost in inundation. Email messages that start with "Fw: FWD: FW: FW FW Fw:" cover most of his inbox; if he clicks on one and scrolls down far enough he can get to the message, a joke about Obama and monkeys, or a cute picture of a kitten. He can sometimes get to the link to photos of the great-grand-children, but after clicking the link he's faced with a moving pop-up box asking him to login, covering the faces of the children. To close that box, he must identify and click on a small "x" in very light grey on a white background. He can use the Web for his bible study and knows it can be used for other purposes, but ubiquitous and intrusive prompts (advertising or otherwise) typically distract him from other tasks.

My grandfather grew up with no experience with media of these kinds, and had no time to develop filters or practices to avoid these intrusions. At his age, it is probably too late to learn a new mindset to throw out mail without a second thought or immediately scroll down a webpage. With a lax regulatory environment and unfamiliar with filtering, he suffers -- financially and emotionally -- from these exploitations on a daily basis. Mail, email, broadcast video, radio and telephone could provide an enormous wealth of benefits for an elderly person living alone: information, entertainment, communication, companionship, edification. But those advantages are made mostly inaccessible.

Younger generations suffer other intrusions of media. Online harassment is widely experienced (its severity varies, by gender among other things); your social media account probably lets you block an account that sends you a threat or other unwelcome message, but it probably doesn't provide mitigations against dogpiling, where a malicious actor encourages their followers to pursue you. Online harassment is important because of the severity and chilling impact on speech, but an analogous problem of over-access exists with other attention-grabbing prompts. What fraction of smartphone users know how to filter the notifications that buzz or ring their phone? Notifications are typically on by default rather than opt-in with permission. Smartphone users can, even without the prompt of the numerous thinkpieces on the topic, describe the negative effects on their attention and well-being.

The capability to filter access to ourselves must be a fundamental principle of online communication: it may be the key privacy concern of our time. Effective tools that allow us to control the information we're exposed to are necessities for freedom from harassment; they are necessities for genuine accessibility of information and free expression. May there be shared blocklists, content warnings, notification silencers, readability modes and so much more.

Labels: mail, harassment, blocklists, accessibility, privacy

From: nick@npdoty.name

Date: 12/11/2017 06:30:00 PM To: Ben Werdmüller Bcc: https://bcc.npdoty.name/

I tried to write the first version of a personal mission statement this morning before work. It's hard. Feedback is a gift! https://werd.io/pages/mission

Awesome. I hadn't considered a personal "mission statement" before now, even though I often consider and appreciate organizational mission statements. However, I do keep a yearly plan, including my personal goals.

Doty Plan 2017: https://npdoty.name/plan

Doty Plan 2016: https://npdoty.name/plan2016.html

I like that your categories let you provide a little more text than my bare-bones list of goals/areas/actions. I especially like the descriptions of role and mission; I feel like I both understand you more and I find those inspiring. That said, it also feels like a lot! Providing a coherent set of beliefs, values and strategies seems like more than I would be comfortable committing to. Is that what you want?

The other difference in my practice that I have found useful is the occasional updates: what is started, what is on track and what is at risk. Would it be useful for you to check in with yourself from time to time? I suppose I picked up that habit from Microsoft's project management practices, but despite its corporate origins, it helps me see where I'm doing well and where I need to re-focus or pick a new approach.

Cheers,

Nick

BCC my public blog, because I suppose these are documents that I could try to share with a wider group.

From: npdoty@ischool.berkeley.edu

Date: 11/27/2017 03:42:00 PM To: Ben Werd Cc: Aaron Parecki, Chris Webber Bcc: https://bcc.npdoty.name/

Hiya Ben,

Yes! I might add, though, that community standards don't need to be enacted entirely in the source code, although code could certainly help. I was in New York earlier this month talking with Cornell Tech folks (for example, Helen Nissenbaum, a philosopher) about exactly this thing: there are "handoffs" between human and technical mechanisms to support values in sociotechnical systems.

What makes federated social networking like Mastodon most of interest to me is that different smaller communities can interoperate while also maintaining their own community standards. Rather than every user having to maintain massive blocklists or trying alone to encourage better behavior in their social network, we can support admins and moderators, self-organize into the communities we prefer and have some investment in, and still basically talk with everyone we want to.

As I understand it, one place to have this design conversation is the Social Web Incubator Community Group (SocialCG), which you can find on W3C IRC (#social) and Github (but no mailing list!), and we talked about harassment challenges at a small face-to-face Social Web meeting at TPAC a few weeks back. Or I'm @npd@octodon.social; there is a special value (in a Kelty recursive publics kind of way) in using a communication system to discuss its subsequent design decisions. I think, as you note, that working on mitigations for harassment and abuse (whether it's dogpiling or fake news distribution) in the fediverse is an urgent and important need.

In a way, then, I guess I'm looking to the creation of new institutions, rather than their dismantling. Or, as cwebber put it:

While I agree that the outsize power of large social networking platforms can be harmful even as it seemed to disrupt old gatekeepers, I do want to create new institutions, institutions that reflect our values and involve widespread participation from often underserved groups. The utopia that "everything would be free" doesn't really work for autonomy, free expression and democracy, rather, we need to build the system we really want. We need institutions both in the sense of valued patterns of behavior and in the sense of community organizations.

If you're interested in helping or have suggestions of people that are, do let me know.

Cheers,

Nick

Some links:

- Social CG: https://www.w3.org/community/socialcg/ or maybe better: https://www.w3.org/wiki/SocialCG

- their issue list, including some abuse or privacy topics: https://github.com/swicg/general/issues

- some previous thoughts on harassment mitigation for the Web: http://bcc.npdoty.name/Dealing-with-harassment-and-spam-on-the-Web

Labels: socialweb, harassment, abuse, handoffs, mastodon